When screenwriter Daniel Turkewitz was working on a script about astronauts struggling to survive in crisis conditions, he enlisted a veteran astronaut as a consultant. That worked so well that when Turkewitz began his new project, a script about Maine seceding from the Union to join Canada, he decided to enlist an expert on the legal niceties of secession. In other words, he decided to enlist a Supreme Court Justice.

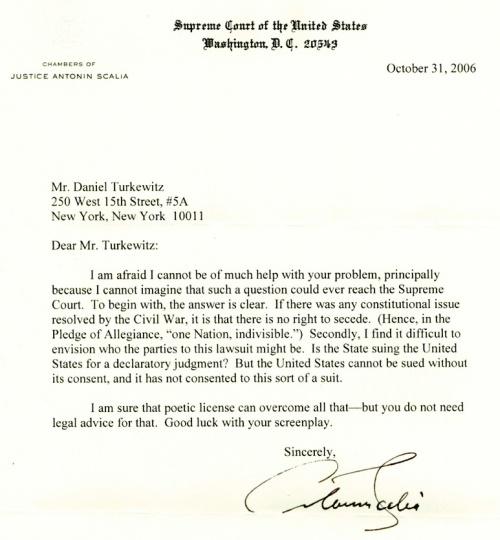

Eight out of nine justices (plus retired Justice Sandra Day O’Connor) ignored Turkewitz’s inquiry about what would happen if a secession case were to reach the Supreme Court. Rather astonishingly, however, Justice Scalia responded with the following letter, which Turkewitz’s brother Eric posted on his blog this week:

Now, as Eric Turkewitz observes, Scalia (not for the first time) might be expressing a minority opinion here. By coincidence, exactly the same question was discussed just a week ago over at the Volokh Conspiracy, where Eugene Volokh suggests that a 144 year old military victory could well be considered something short of a definitive resolution of a constitutional issue.

A grateful hat tip to Jon Shea, who called my attention to this remarkable story in a comment to an earlier post.

Scalia’s given a very big response to a really Big Question.

I think it’s odd that they chose Maine as the State in question. I grew up in Vermont (sort of), and having done so I would nominate it as the state most likely to secede from the Union. Mainly because there were active secession movements on both the right and the left when I was growing up there.

I’m going to forgo a long tract on the history of Vermont’s independence from MA and NY and just say that most Vermonters take it as a matter of faith that Vermont is the only state in the union that the US is contractually obligated to let go. (I’m also going to forgo a long tract on the way that Vermont affected modern immigration policy, but if you ever want to know why our quota based system exists you can ask me- I know a few things about this that very few immigration scholars do, as a result of having researched certain Vermonters.)

At any rate, it is an article of faith for a large number of Vermonters that “if we want out”, “they have to let us go.” I think I might have first started thinking about politics and power when I first heard that claim.

I may be misremembering my history, but I believe Maine is being discussed because it joined the Union by seceding from Canada…so it has a fickle history already.

Yes, RL, but Vermont joined the union after fighting a successful war of independence against states belonging to the US. It is one of two states to have been an independent sovereign state before becoming a state. Texas is the other.

Tagore,

What about Hawaii or California?

Texans say the same thing as an article of faith as well. Do others states say the same thing?

I don’t think Maine seceded from Canada. It was part of the Massachusetts Bay Colony in the 1600s and later a part of the state of Massachusetts. It split off to become its own state in the 1800s as part of the Missouri compromise.

George is correct. Maine was never a part of Canada, though after the revolution there were border disputes between the US and Canada involving Maine.

I’m a Texan, by birth and residence, and this nonsense about Texas having a special right to secede has been around a very long time.

Tagore-

Interesting; that Vermont fought a war of independence from other states is news to me. I know Vermonters were very active in fighting the Brits in the revolution and Vermont existed as a republic during the Articles of Confederation. Vermont ratified the Constitution within months of the last of the first 13 states, becoming the 14th state. So maybe their war for independence occurred after the revolution.

However, one thing I know for certain is that Vermont entered the union on the same terms re: the right to secede as all the other states. They have no right of seccession, contractual or otherwise.

Now for the big issue that Eugene Volokh cast doubts upon: whether the “right” of secession was definitively resolved by the Civil War.

The constitutional question of the right to secede was resolved long before the Civil War. The North’s victory simply finalized its enforcement of the clear intent of the authors and ratifiers of the Constitution. It did so by crushing the South’s attempt to use force to impose its “right-to-secede” interpretation on the nation in order to preserve slavery and the political/economic power of the slavocracy elites.

I’ve just finished Akhil Reed Amir’s “America’s Constitution” which I highly recommend. He (and other constitutional scholars before him) destroys the “right-to-secede” arguments; I won’t summarize them here.

But I will use an analogy to illustrate the point: the Constitution represented a contract among the original 13 states (and all 37 that followed) in which those states gave up something in return for the benefits they sought under the new Constitution. Once a state had ratified the Constitution, they entered into a contract with all the other states that did so. And as with any contract, a single party cannot withdraw from or violate the contract without consent of ALL the other parties.

What is the basis for interpreting the Constitution as a mutually binding contract? The most powerful evidence lies in the debates between the Federalists (who backed adoption of the Constitution) and the anti-federalists (who opposed it). These debates first arose during the Congress that wrote and proposed the Constitution, continued through the national debate of which the Federalist papers represent the most authoritative account of the Federalist point of view, and the debates at the state level during each state’s ratification convention.

Again, I won’t summarize the debate, but suffice it to say that one of the central arguments against ratification mounted by the anti-federalists was that states would be surrendering the right of sucession that they had enjoyed under the Articles of Confederation, (which would be replaced by the Constitution).

Obviously, the anti-federalists went 0 for 13 in this argument to remain in Confederation since all 13 states ratified.

Moreover, the Civil War was not the first secession crisis in US history. The most serious antebellum crisis was instigated by the perennially wild-eyed South Carolinians who threatened secession in the 1830s. This threat was terminated by the threat of force by southern, slave-holding Andrew Jackson who held the same opinion of the “right-to-secede” argument as Lincoln would 30 years later.

Finally, there is one Supreme Court decision I know of that addresses the right to secede, Texas v Smith (1869), in which the court rejected the argument by my fellow secession-obsessed Texans.

One note: while there is clearly no right of secession under the Constitution, I think there are good arguments that there is an extra-constitutional, natural right of the people ( a right which underlies the Declaration of Independence and American democratic theory more generally) to overthrow their government through revolution.

Well, all of the fun of secession goes right out the window when you realize that you would have to take your fair share of the national debt.

There are two ways to secede. One is by screwing up the state so much that the rest of the country would be glad to see you go (see today’s California), the other way is by winning a military victory over the rest of the country, to force them to let you go. No single state is likely to accomplish the latter.