I was recently asked to speak at the awards ceremony for the winners of the Witwatersrand math competition. This presented a particular challenge, because there were winners in age groups ranging from nine-year-olds to college students. Here is the talk I ended up giving:

Author Archive for Steve Landsburg

I take it that the following states are undecided:

Pennsylvania

Georgia

Michigan

North Carolina

Wisconsin

Nevada

By my calculations, this election is a tie if Trump wins (precisely) any of the following three subsets:

A = {Pennsylvania, Georgia, Michigan}

B = {Pennsylvania, Georgia, Wisconsin, Nevada}

C= {Pennsylvania, Michigan, Wisconsin, Nevada}

It is a Trump victory if Trump wins any of the following:

1) Any superset of A, B or C.

2) Any superset of {Michigan, Georgia, North Carolina, Wisconsin}

3) Any superset of {Michigan, Georgia, North Carolina, Nevada}

I went to bed believing that 98 – 47 = 41, and therefore had this all wrong, but I think it’s right now. Does anyone want to check my arithmetic?

I like my eggs poached and slightly runny. If you feel like I just wasted a moment of your time, you might want to stop reading. What follows is mostly opinion, and I’m not sure my opinions about politics are worth any more of your time than my opinions about eggs.

That said:

1) Liberalism — by which I mean the societal presumption that it’s okay for people to disagree about fundamental things and not have to kill each other over it — and even better that they can live in harmony and respect their differences — is only a few hundred years old. It is also, I suspect, a lot more fragile than it appears to those of us who have had the good fortune to live in a time and place where we could take it for granted.

2) Not coincidentally, prosperity — by which I mean that a great many people are not starving — is approximately the same age, and likely to be just as fragile. A few hundred years is, in historical time, the blink of an eye.

There are (at least) two ways to test the efficacy of a vaccine. The Stupid Way is to administer the vaccine to, say, 30,000 volunteers and then wait to see how many of them get sick. The Smarter Way is to adminster the vaccine to a smaller number of (presumably much better-paid) volunteers, then expose them to the virus and see how many get sick.

A trial implementing the Smart Way is getting underway at Imperial College London. In the United States, we do things the Stupid Way, at least partly because of the unaccountable influence of a tribe of busybodies who, having nothing productive to do, spend their time trying to convince people that thousands of lives are worth less than dozens of lives. Those busybodies generally refer to themselves as Ethicists, but I think it’s always better to call things by informative names, so I will refer to them henceforth as Embodiments of Evil.

Last night, while I was attempting to calculate the amount of damage that these Embodiments of Evil have caused, I was interrupted by a knock on my door. It turned out to be a man from Porlock, who wanted to consult me on some mundane issue. At first I tried to turn him away, explaining that I was in the midst of a difficult calculation and could not be distracted. But my visitor brought me up short by reminding me that the economist’s job is not just to lament bad policies, it’s also to figure out ways to circumvent them. So we put our heads together and this is what we came up with:

First, design a vaccine trial that is, to all appearances, set up the Stupid Way. We vaccinate people, we let them go their own ways, and we track what happens. But we add one twist: Any volunteer who gets sick after being vaccinated receives an enormous payment. Call it something like “Compassionate Compensation”.

Here are the advantages:

Continue reading ‘Vaccine Testing: The Smart and Sneaky Way’

Here are the opening paragraphs of my (paywalled) op-ed in today’s Wall Street Journal.

For nearly four years, I’ve looked forward to voting against Donald Trump. But Joe Biden keeps testing my resolve.

It isn’t only that I think Mr. Biden is frequently wrong. It’s that he tends to be wrong in ways that suggest he never cared about being right. He makes no attempt to defend many of his policies with logic or evidence, and he deals with objections by ignoring or misrepresenting them. You can say the same about President Trump, but I’d hoped for better.

The great tragedy of the Trump administration has been that the President’s obvious mental incapacity has tended to discredit, in the minds of the public, even the good policies that he (apparently randomly) chooses to endorse. As a result, many good policies will never get the consideration they’re due.

For example: Trump happens to be right that we can design a system a whole lot better than Obamacare. But he’s never explained why, and he’s never even attempted to sketch out what such a system might look like. This (appropriately, and probably accurately) makes him appear to be an idiot, and therefore (inappropriately) leads the public to dismiss meaningful health care reform as an idiotic policy.

Likewise: Trump happens to be right that lockdowns and other mandates have enormous costs, which need to be weighed against the benefits of fighting a pandemic. But instead of focusing on that important point, he’s garbled it all up with the ridiculous notion that you’d have to be dumb to wear a mask (and no, his occasional weasel words on this subject do not erase his primary message). This (appropriately, and probably accurately) makes him appear to be an idiot, and therefore (inappropriately) leads the public to dismiss meaningful cost-benefit analysis as an idiotic exercise.

There are a thousand more examples; feel free to share your favorites in comments.

The next time somebody asks me why there have to be billionaires, I will point that person to this tweet from Elon Musk:

Musk went ahead and invested about $100 million in SpaceX and $6 million in Tesla — totaling about half of his proceeds from the sale of PayPal, in which he was an early investor.

Who invests $100 million in a project that has a 10% chance of success? Answer: Essentially nobody who doesn’t believe that success will bring a reward of at least $1 billion.

I devoutly wish that Ruth Bader Ginsburg had lived on for a very long time. She was fair-minded, thoughtful, and occasionally brilliant. I valued her reasoning even when I disagreed with her conclusions, and because she was a careful thinker, I am confident that there were times when she was right and I was wrong.

I devoutly wish that Donald Trump were not the president of the United States, largely because he is everything that Ginsburg was not.

But clouds have silver linings, and I take great solace in the fact that Trump will (probably) appoint Ginsburg’s successor. History suggests that a Trump appointee will share the Ginsburg characteristics I most admire, and that a Biden appointee would probably not. The world is a complicated place.

This Saturday at 2PM Eastern time, I’ll be talking to the Philadelphia Association for Critical Thinking on “Why is There Something Instead of Nothing?”

Unfortunately, times are such that I’ll have to give my talk over Zoom. Happily, this means that no matter where you are in the world, you can attend. Register by visiting the upcoming meetings page and scrolling down to “Click Here to Register” (near the very bottom), or just visit the registration page. Registration is free but required.

As my good deed for today, I’m posting a solution to a problem that I’m sure is plaguing others. I hope Google points them here.

I’ll say this much for brick-and-mortar booksellers: Not one of them ever sold me a book, then showed up at my house two years later, pulled the book off the shelf and started highlighting passages for me. I can’t say as much for Amazon, which has been selling me books for many years and has suddenly decided to highlight passages in all of them. Effectively, they’ve vandalized every book they’ve ever sold me.

Yes, I know about the checkbox in the settings for “Show Popular Highlights”. (This is in the Android Kindle App.) Yes, I have that box unchecked. I am not an idiot. Unchecking the box has no effect. Checking it and then unchecking it again has no effect. The highlights remain highlighted.

Here are some other things that don’t work: Clear the app cache. Reboot the phone. Express rage.

So I called Amazon customer service and had the good luck to hook up with Brandi G., who was fantastic. She instantly understood the problem, instantly understood everything I had tried to do to fix it, and, unlike what I’ve come to expect from customer service reps pretty much everywhere, she did not insist that I try all the same things again. Instead, she suggested that I uninstall the app completely and reinstall it, and she stayed with me on the phone to see how things would turn out. Presto! Problem solved. Yay Brandi.

Then an hour later, the popular highights came back.

So I uninstalled and re-installed about six more times (because that’s the kind of guy I am) and finally called Amazon again. This time I had the bad luck to hook up with Devan J., who kept me on the phone for 35 minutes, mostly in silence while he researched the problem. (When I suggested that we hang up and he could call me back when he had an answer, he insisted that I stay on the line, to no apparent purpose.) One of the first things I asked him was: What if I install an older version of the app? No, said Devan, unfortunately that’s impossible.

Like an idiot, I spent about 24 hours believing him. Then I decided to go ahead and do it. Here is the solution:

1) Fully uninstall the app. This means going to the phone settings, then Apps, then Amazon Kindle. First choose “Force Stop” and then “Uninstall”.

2) Go to apkpure.com, search for the Kindle app, and you’ll be presented with a great variety of choices, all representing different vintages of the same app. I chose one from June 2020, two months ago, well before my problems started. Click to download, click to install, and voila. Problem solved.

I hope this works for you too.

Coming soon, I hope: Tricks I’ve discovered for setting up a new Windows 10 machine, which has been something like a fulltime job for me for the past two weeks. Why can’t things just work out of the box?

A short time ago, in a Universe remarkably similar to our own, a team of researchers investigated racial differences in cognitive skills and concluded, with high degrees of certainty and precision, that the correlation between race and intelligence is zero. They submitted their results to a journal called Science, which is remarkably similar to the journal called Science in our own Universe. The paper was accepted for publication, but the editors saw fit to issue this public statement:

We were concerned that the forces that want to downplay the differences between the races as well as the need for racial segregation would seize on these results to advance their agenda. We decided that the benefit of providing the results to the scientific community was worthwhile.

Which of the following best captures the way you feel about that statement?

A. Bravo to the editors for advancing the cause of truth, even if it might be misused.

B. Boo to the editors for even thinking about suppressing the truth, even if the truth might be misused.

C. WHAT?!?!? Since when is a failure to share the editors’ political priorities a “misuse” in the first place?

D. Both B and C.

E. Other (please elaborate).

My vote is for D. It is outrageously wrong for the editors to even consider using the resources of their journal to promote their private political agenda. It is doubly wrong for them to even consider doing so by suppressing a paper they would otherwise accept. And it is triply wrong for them to even consider imposing on the owners and readers of the journal to support a political agenda that some of those owners and readers will no doubt find deplorable.

I happen to be one of those who deplore the expressed agenda, but that has nothing to do with my point here. The outrage would be exactly as great if the editors were focused on protecting capitalism instead of segregation.

Now let’s come back to our own Universe, where the editors of Science (the real Science) accepted a paper suggesting that a large fraction of the population might already have a sort of pre-immunity to Covid 19, and somehow saw fit to issue the following statement:

We were concerned that forces that want to downplay the severity of the pandemic as well as the need for social distancing woud seize on the results to suggest that the situation was less urgent. We decided that the benefit of providing the model to the scientific community was worthwhile.

As I said, the two Universes are eerily similar. The statements made by the editorial boards in both Universes seem about equally outrageous to me.

The real-world editors, if they cared what I thought, might want to respond that my analogy fails because “the need for racial segregation” is a political stance, whereas “the need for social distancing” is a scientific one. If so, they’d simply be wrong. Biologists have no particular insight into whether people would be happier in a world with both a little more Covid and a few more hugs. If any group is uniquely qualified to estimate the terms of that tradeoff, it’s the economists — but I wouldn’t want the editors of an economics journal making this kind of call either.

I’m glad that the editors did the right thing. I’m appalled they even considered doing the wrong thing, and concerned that this means they might do the wrong thing in the future, and might have done so in the past. It is not okay to suppress truth in the furtherance of a political agenda. It is not okay to presume that all good people share in your agenda, or to co-opt other people’s resources in order to advance it.

(Hat tip to David Friedman, whose blog made me aware of this.)

Walter Block is under fire from a bunch of very silly people, for reasons that he recounts in this week’s Wall Street Journal.

Unfortunately, if you’re not a Journal subscriber that link probably won’t work for you. Fortunately, it doesn’t matter, because these people are as unoriginal as they are silly, and the issues are pretty much the same as they were when a bunch of equally silly people ganged up on Walter six years ago. So you’ll be pretty much caught up if you just re-read the accounts from back then.

You could, for example, re-read my 2014 blog posts titled Block Heads and Chips Off the Block. I’ll even make this easier for you by reposting the first one right here:

The righteously irrepressible Walter Block has made it his mission to defend the undefendable, but there are limits. Chattel slavery, for example, will get no defense from Walter, and he recently explained why: The central problem with slavery is that you can’t walk away from it. If it were voluntary, it wouldn’t be so bad. In Walter’s words:

The righteously irrepressible Walter Block has made it his mission to defend the undefendable, but there are limits. Chattel slavery, for example, will get no defense from Walter, and he recently explained why: The central problem with slavery is that you can’t walk away from it. If it were voluntary, it wouldn’t be so bad. In Walter’s words:

The slaves could not quit. They were forced to ‘associate’ with their masters when they would have vastly preferred not to do so. Otherwise, slavery wasn’t so bad. You could pick cotton, sing songs, be fed nice gruel, etc. The only real problem was that this relationship was compulsory.

A group of Walter’s colleagues at Loyola university (who, for brevity, I will henceforth refer to as “the gang of angry yahoos”) appears to concur:

Traders in human flesh kidnapped men, women and children from the interior of the African continent and marched them in stocks to the coast. Snatched from their families, these individuals awaited an unknown but decidedly terrible future. Often for as long as three months enslaved people sailed west, shackled and mired in the feces, urine, blood and vomit of the other wretched souls on the boat….The violation of human dignity, the radical exploitation of people’s labor, the brutal violence that slaveholders utilized to maintain power, the disenfranchisement of American citizens, the destruction of familial bonds, the pervasive sexual assault and the systematic attempts to dehumanize an entire race all mark slavery as an intellectually, economically, politically and socially condemnable institution no matter how, where, or when it is practiced.

So everybody’s on the same side, here, right? Surely nobody believes the slaves were voluntarily snatched from their families, shackled and mired in waste, sexually assaulted and all the rest. All the bad stuff was involuntary and — this being the whole point — was possible only because it was involuntary. That’s a concept with broad applicability. One could, for example, say the same about Auschwitz. Nobody would have much minded the torture and the gas chambers if there had been an opt-out provision. And this is a useful observation, if one is attempting to argue that involuntary associations are the root of much evil.

|

|

Thoughts on what it takes to be a successful presidential candidate, circa 1980.

From Joseph Kraft:

The emergence of President Carter and Ronald Reagan as the nearly certain nominees of their parties expresses not a failure of the system, but a true translation of how much the majority prefers nice men to effective measures.

From Florence King:

We want a president who is as much like an American tourist as possible. Someone with the same goofy grin, the same innocent intentions, the same naive trust; a president with no conception of foreign policy and no discernible connection to the U.S. government, whose Nice Guyism will narrow the gap between the U.S. and us until nobody can tell the difference.

People who have a lot of money very rarely give it away. Some invisible hand prevents them.

| —Iris Murdoch |

| Henry and Cato |

This was Woodstock. As Jeffrey Tucker reminds us, Woodstock took place in the midst of a global pandemic that claimed more American lives than has Covid-19 (at least so far) — at a time when the population was much smaller . After correcting for population size and demographics, Tucker estimates the Hong Kong flu epidemic of 1969 killed the equivalent of 250,000 contemporary Americans, compared to under 100,000 so far for the current affliction.

Yet in 1969, American life went on pretty much as normal. As Tucker points out:

Stock markets didn’t crash because of the flu. Congress passed no legislation. The Federal Reserve did nothing. Not a single governor acted to enforce social distancing, curve flattening (even though hundreds of thousands of people were hospitalized), or banning of crowds. No mothers were arrested for taking their kids to other homes. No surfers were arrested. No daycares were shut even though there were more infant deaths with this virus than the one we are experiencing now. There were no suicides, no unemployment, no drug overdoses attributable to flu.

Media covered the pandemic but it never became a big issue.

The Woodstock producers flew in a dozen doctors to have on hand in case of a fast-spreading virus, but they seem to have given no serious thought to the prospect of cancelling.

Why such a difference between then and now? Tucker suggests a few possible culprits (the 24 hour news cycle, political and cultural shifts, etc.), but the first thing that came to my mind was that folks today are a whole lot richer than folks in 1969, and can therefore much better afford to take a few months off. If the average worker in 1969 had taken a four-month unscheduled vacation without any assistance, he’d have gone hungry — and the amount of available assistance was limited by the fact that everyone else was a lot poorer then too.

Here are the key facts we need to test that theory:

- The income of the average American today is about two-and-a-half times what it was in 1969.

- The income elasticity of the value of life is estimated to be somewhere between .5 and 1.0, and probably toward the lower end of that range for a developed country like the United States. I’ll take it to be .6. Here the “value of life” refers to the amount people are willing to pay to avoid a given small chance of death, and the elasticity estimate means that the value of your life is (approximately) proportional to I.6, where I is your income.

Taken together, these facts imply that the value of a life in 1969 was about 58% of what it is today, which in turn implies that people would have been willing to put up with only 58% as much lost income in exchange for the same amount of safety. If you’re willing to tolerate six months without a paycheck to avoid, say, a 1% chance of death, then your 1969 self would have been willing to tolerate only about three-and-a-half months. If avoiding that 1% chance of death requires, say, a five-month lockdown (or any other length longer than three-and-a-half months but shorter than six), then you’re going to favor that lockdown, though you’d have scoffed at the thought of it in 1969.

Even this fails to account for another factor: A national shutdown of a given length would have been a lot costlier in 1969 than it is in 2020, when a good 30% of us can work from home. Perhaps a six-month lockdown only costs us (on average), say, three month’s income. (I pulled that “three months” out of my hat. I’m sure with a little research I could have done better.) If that’s what we’re willing to tolerate for a given amount of safety, then our 1969 selves would have tolerated only a one-and-three-quarter months’s income loss, which might have meant something like a two month lockdown. Where we’d tolerate six months, they’d tolerate only two.

In other words: Nobody considered locking down the economy in 1969 because they couldn’t afford to (or more precisely, given their relative poverty, they preferred to spend their wealth on other things). Today’s lockdown is widely supported because it’s a luxury we’ve grown rich enough to afford. In other words, the lockdown is yet another triumph of capitalism.

That, at least, is what the back of my envelope says. I expect there are people who have thought about this a whole lot harder than I have. I hope we hear from some of them.

Herewith an excerpt from Chapter LIV of The Way We Live Now, by Anthony Trollope, first published in 1875.

The background:

Mr. Augustus Melmotte, reputed to be in possession of a great fortune, of which both the magnitude and the provenance are cloaked in considerable mystery, has declared his candidacy for the Parliamentary seat of Westminster. Some say he’s much less wealthy than he claims to be, others that his wealth has all been effectively stolen from stakeholders in the vast enterprises that he’s run into the ground. His supporters say he’s a financial genius, and that this is a sufficient qualification for the job. He is accompanied on the campaign trail by Lord Alfred Grendall, a member of the Conservative establishment from Indiana London who has hitched his wagon to Mr. Melmotte’s star:

There was one man who thoroughly believed that the thing at the present moment most essentially necessary to England’s glory was the return of Mr. Melmotte for Westminster. This man was undoubtedly a very ignorant man. He knew nothing of any one political question that had vexed England for the last half century, — nothing whatever of the political history which had made England what it was at the beginning of that half century. Of such names as Hampden, Somers and Pitt he had hardly ever heard. He had probably never read a book in his life. He knew nothing of the working of parliament, nothing of nationality, — had no preference whatever for one form of government over another, never having given his mind a moment’s trouble on the subject. He had not even reflected how a despotic monarch or a federal republic might affect himself, and possibly did not comprehend the meaning of those terms. But yet he was fully confident that England did demand and ought to demand that Mr. Melmotte should be returned for Westminster. This man was Mr. Melmotte himself.

Continue reading ‘The More Things Change…’

For cost-benefit analysis, the usual ballpark figure for the value of a life is about $10,000,000. But I keep hearing it suggested that when it comes to fighting a disease like Covid-19, which mostly kills the elderly, this value is too high. In other words, an old life is worth less than a young life.

I don’t see it.

People seem to have the intuition that ten years of remaining life are more precious than one year of remaining life. That’s fine, but here’s a counter-intuition: An additional dollar is more precious when you can spend it at the rate of a dime a year for ten years than when you’ve got to spend it all at once — for example, if your time is running out. (This is because of diminishing marginal utility of consumption within any given year). So being old means that both your life and your dollars have become less precious. Because we measure the value of life in terms of dollars, what matters is the ratio between preciousness-of-life and preciousness-of-dollars (or more precisely preciousness-of-dollars at the margin). If getting old means that the numerator and the denominator both shrink, it’s not so clear which way the ratio moves.

Instead of fighting over intuitions, let us calculate:

Suppose you’re a young person with 2 years to live and 2N dollars in the bank, which you plan to consume evenly over your lifetime, that is at the rate of $N per year. I’ll write your utility as

Suppose also that you’re willing to forgo approximately pX dollars to avoid a small probability p of immediate death. Then (by definition!) X is the value of your life. (The reasons why this is the right definition are well known and have been discussed on this blog before. I won’t review them here.) This means that

= U(N,N) – (pX/2)U1(N,N) – (pX/2)U2(N,N)

(where the last equal sign should be read as “approximately equal” and the Ui are partial derivatives).

Because you’ve optimized, U2(N,N) = U1(N,N), so we can write

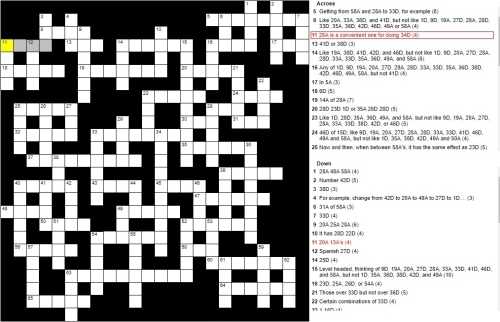

The victors in last week’s crossword challenge were:

First place, with a score of 276/276: A tie between Dan Williams and Richard Kennaway.

Second place, but heartbreakingly close, with a score of 274/276: Another tie, between Tim Goodwyn and the team of Dan Grayson & Carol Livingstone

Third place: Paul Epps

Fourth Place: Eric Dinsdale

Fifth Place: A tie between Paul Grayson and Biopolitical

Thanks to all of the above and all the rest who participated.

Some notes:

1) There are 276 white boxes in the puzzle. I scored one point per box. Other scoring systems are possible, such as one point per word.

2) I am open to the possibility that some of the answers marked wrong are just as good as the answers counted as right. I’ll try to give this some thought.

Why do some people sign up to have their brains frozen for possible future resurrection, while others don’t? You might think it’s because the first group has more faith in future technology, but Scott Alexander has survey data to suggest otherwise. Active members of the forum lesswrong.com, many of whom had pre-paid for brain freezing, thought there was about a 12% chance it would work. Among members of a control group with no interest in the subject, the estimate was about 15%.

In a long and characteristically thoughtful blog post, Alexander concludes that:

Making decisions is about more than just having certain beliefs. It’s also about how you act on them.

and

The control group said “15%? That’s less than 50%, which means cryonics probably won’t work, which means I shouldn’t sign up for it.” The frequent user group said “A 12% chance of eternal life for the cost of a freezer? Sounds like a good deal!”

Goofus (says Alexander) treats new ideas as false until somebody provides incontrovertible evidence that they’re true. Gallant does cost-benefit analysis and reasons under uncertainty.

So a few weeks ago when we all thought that the chance of a global pandemic was, oh, about 10%, Goofus said “10%? That’s small. We don’t have to worry about it.”, while Gallant would have done a cost-benefit analysis and found that putting some tough measures into place, like quarantine and social distancing, would be worthwhile if they had a 10 or 20 percent chance of averting catastrophe.

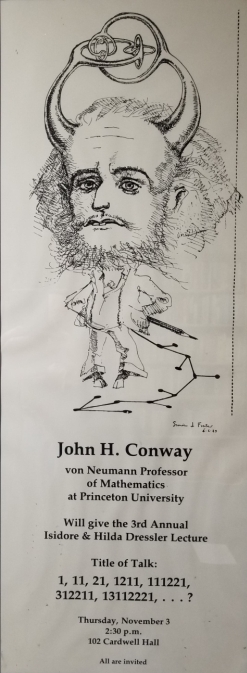

The poster to the left hangs on the wall of my office. Can you figure out the pattern to the sequence? Now can you estimate the size of the nth entry?

The poster to the left hangs on the wall of my office. Can you figure out the pattern to the sequence? Now can you estimate the size of the nth entry?

John Horton Conway died yesterday, a victim of Covid-19. His unique mathematical style combined brilliance and playfulness in equal measure. I came across his “soldier problem” at an impressionable age, and was astonished by the beauty of the solution. You’ve got an infinite sheet of graph paper, with one horizontal grid line marked as the boundary between friendly and enemy territory. You can place as many soldiers as you like in friendly territory, at most one to a square. Now you can start jumping your soldiers over each other — a soldier jumps horizontally or vertically, over an adjacent soldier (who is then removed from the board) into an empty square. The goal is to advance at least one soldier to the fifth row of enemy territory. Conway’s proof that it can’t be done struck me then as utterly beautiful, utterly unexpected, and a compelling reason to learn more about this mathematics business.

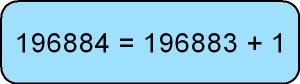

He invented the Game of Life. He invented the system of surreal numbers, a vast generalization of the usual real numbers, designed for the purpose of assigning values to positions in games but adopted by mathematicians for purposes well beyond its original design. (Don Knuth’s book on the subject is a classic, and easy reading). His Monstrous Moonshine conjecture is the reason I own a t-shirt that says:

which I am prepared to argue is the most remarkable equation in all of mathematics. He was the first person to prove that every natural number is the sum of 37 fifth-powers. More than a century after mathematicians first gave a complete classification of two-dimensional surfaces, Conway (together with George K. Francis) found a much better proof. He worked in geometry, analysis, algebra, number theory and physics. And reportedly, he could solve a Rubik’s Cube behind his back, after inspecting it for a few seconds.

Gone now, along with John Prine — another icon of my youth — and too many others. I got the word about Conway just as I was about to go to bed, and am typing this in a state of exhaustion. If I were more awake, it would be more coherent, but it will have to do.

Feeling isolated? Perhaps a crossword puzzle will help.

Click on the image to do the crossword puzzle on line, or click here for a printable pdf.

If you do the puzzle on line, you can click the “submit” button to bring up a form where you can enter your name and submit your solution. I will find a suitable way to honor the best submissions.

Meanwhile, please do not post spoilers!!!.

Update: Thanks to biopolitical, who pointed out that there was a problem with the clue for 24A. That clue is fixed now.

Thanks also to my Mom, who informed me that the pdf wasn’t printing properly. That’s fixed now too.

[I am happy to turn this space over to my former colleague and (I trust) lifelong friend Romans Pancs, who offers what he describes as

a polemical essay. It has no references and no confidence intervals. It has question marks. It makes a narrow point and does not weigh pros and cons. It is an input to a debate, not a divine revelation or a scientific truth.

I might quibble a bit — I’m not sure there’s such a thing as a contribution to a debate that nobody seems to be having. I’d prefer to see this as an invitation to start a thoughtful and reasoned debate that rises above the level of “this policy confers big benefits; therefore there’s no need to reckon with the costs before adopting it”. That invitation is unequivocally welcome. ]

| —SL |

The Main Argument

It is a crime against humanity for governments to stop a capitalist economy. It is a crime against those whom the economic recession will hit the hardest: those employed in the informal sector, those working hourly customer service jobs (e.g., cleaners, hairdressers, masseurs, music teachers, and waiters), the young, the old who may not have the luxury of another year on the planet to sit out this year (and then the subsequent recession) instead of living. It is a crime against those (e.g., teachers and cinema ushers) whose jobs will be replaced by technology a little faster than they had been preparing for. It is a crime against the old in whose name the society that they spent decades building is being dismantled, and in whose name the children and the grandchildren they spent lifetimes nourishing are subjected to discretionary deprivation. Most importantly, it is a crime against the values of Western democracies: commitment to freedoms, which transcend national borders, and commitment to economic prosperity as a solution to the many ills that had been plaguing civilisations for millennia.

Capitalism and democracy are impersonal mechanisms for resolving interpersonal (aka ethical) trade-offs. How these trade-offs are resolved responds to individual tastes, with no single individual acting as a dictator. Governments have neither sufficient information, nor goodwill, nor the requisite commitment power, nor the moral mandate to resolve these tradeoffs unilaterally. Before converting an economy into a planned economy and trying their hand at the game that Soviets had decades to master (and eventually lost) but Western governments have been justly constrained to avoid, Western governments ought to listen to what past market and democratic preferences reveal about what people actually want.

People want quality adjusted life years (QALY). People pay for QALY by purchasing gym subscriptions while smoking and for safety features in their cars while driving recklessly. Governments want sexy headlines and money to buy sexy headlines. Experts want to show off their craft. But people still want QALY, which means kids do not want to spend a year hungry and confined in a stuffy apartment with depressed and underemployed parents; which means the old want to continue socialising with their friends and, through the windows of their living rooms, watch the life continue instead of reliving the WWII; which means the middle-aged are willing to bet on retaining the dignity of keeping their jobs and taking care of their families against the 2% chance of dying from the virus.

Suppose 1% of the US population die from the virus. Suppose the value of life is 10 million USD, which is the number used by the US Department of Transportation. The US population is 330 million. The value of the induced 3.3 million deaths then is 33 trillion USD. With the US yearly GDP at 22 trillion, the value of these deaths is about a year and a half of lost income. Seemingly, the country should be willing to accept a 1.5 year-long shutdown in return for saving 1% of its citizens.

The above argument has three problems that overstate the attraction of the shutdown:

- The argument is based on the implicit and the unrealistic assumption that the economy will reinvent itself in the image of the productive capitalist economy that it was before the complete shutdown, and will do so as soon as the shutdown has been lifted.

- The argument neglects the fact that the virus disproportionately hits the old, who have fewer and less healthy years left to live.

- The argument neglects the fact that shutting down an economy costs lives. The months of the shutdown are lost months of life. Spending a year in a shutdown robs an American of a year out of the 80 years that he can be expected to live. This is a 1/80=%1.25 mortality rate, which the society pays in exchange for averting the 1% mortality rate from coronavirus.

It is hard to believe that individuals would be willing to stop the world and get off in order to avert a 1% death rate. Individuals naturally engage in risky activities such as driving, working (and suffering on-the-job accidents), and, more importantly, breathing. Allegedly, 200,000 Americans die from pollution every year. Halting an economy for a year would save all those people. Stopping the economy for 15 years would be even better, and save all the lives that coronavirus would take. Indeed, stopping the economy is a gift that keeps giving, every year, while coronavirus deaths can be averted only once. Yet, with the exception of some climate change fundamentalists, there were no calls for stopping the economy before the pandemic.

The economy shutdown due to coronavirus seems to be motivated by the same lack of faith in progress and society’s ability to mobilise to find technological solutions (if not for this strain of the virus then for the future ones), and by the Catholic belief in the virtue of self-flagellation of the kind sported by climate-change fundamentalists of Greta’s persuasion. This lack of faith is not wholly the responsibility of governments and is shared by the citizens.

1. Bernie Sanders says (repeatedly) that he wants the United States to be more like Sweden. Bring it on! No estate or inheritance taxes, no minimum wage, a much higher ratio of consumption taxes to income taxes, an income tax system that is by some reasonable standards far less progressive, school choice, high deductibles and copays for medical care, lighter regulatory burdens and free trade. And a government that has shrunk by a third over the last few decades, ever since the Swedes got fed up with the economic stagnation that went hand-in-hand with the old-style Swedish socialism of Sanders’s fantasies. Farad Zakaria says all this and more in a spectacularly good op-ed at the Washington Post.

2. The ever-thoughtful Robin Hanson observes that if a whole lot of us are going to be struck by COVID-19, it would be a whole lot better for us not to all get sick at once. If I were pretty sure (maybe a bit surer than I am now) that I was destined to get sick eventually, I’d much rather have it be now than a few months later when 70% of my neighbors — including 70% of medical personnel, 70% of food providers, etc. — are all sick too. So maybe it’s time to start incentivizing people to expose themselves, get their illnesses over with, and be immune when the rest of us need them. Robin points out there’s plenty of precedent — parents used to be (and for all I know, still are) routinely advised that when one kid gets chicken pox, it’s a good idea to expose the others, because it’s easier to treat three at once then three in succession. (Of course the parents are aiming to bunch while Robin is aiming to minimize bunching, but the point in both cases is to think about how much bunching is optimal and then aim for it.) More here, with, as usual in a Hanson post, much worth pondering.

|

|

If Bernie Sanders wants to say that Fidel Castro occasionally did something good, while acknowledging that he often did things that were very bad, I think that’s a reasonable position. (It might also be reasonable to say that Adolf Hitler occasionally did something good, though offhand I can’t think of a good example.)

But surely — surely — if it’s reasonable to say this about Castro, then it’s enormously more reasonable to say that there were good people among the protestors in Charlottesville, Virginia, while acknowledging that there were also some very bad people. Because I have not the slightest shred of a doubt that the fraction of people on either side of that Charlottesville protest who were basically good is enormously greater than the fraction of Castro’s policies that were basically good.

You might want to argue that it’s not okay to acknowledge any goodness at all in a Hitler or a Castro or a large crowd of people that includes some number of violent neo-Nazis. I wouldn’t agree with you, because I think it’s always okay to acknowledge anything that happens to be true. But if that’s your position, you have to decide where to draw the line, and if you draw the line in a way that puts Trump beyond the pale, then Sanders is way beyond the pale.

In other words, I see how you can excommunicate both of them, I see how you can excommunicate just Sanders, and I see how you can excommunicate neither. My preference is neither. If your preference is otherwise, we can cheerfully disagree. But if you want to excommunicate just Trump, I’m very skeptical that you’re applying anything like a consistent standard. Feel free to prove me wrong in comments.