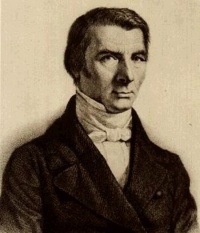

A month ago, I prematurely celebrated the 209th birthday of the great economic communicator Frederic Bastiat. Today (unless I’ve screwed up a second time) is actually his birthday. A good way to celebrate is to read (or reread!) Bastiat’s little masterpiece Economic Sophisms; you will never see the world the same way again. Here’s a taste:

A month ago, I prematurely celebrated the 209th birthday of the great economic communicator Frederic Bastiat. Today (unless I’ve screwed up a second time) is actually his birthday. A good way to celebrate is to read (or reread!) Bastiat’s little masterpiece Economic Sophisms; you will never see the world the same way again. Here’s a taste:

At a time when everyone is trying to find a way of reducing the costs of transportation; when, in order to realize these economies, highways are being graded, rivers are being canalized, steamboats are being improved, and Paris is being connected with all our frontiers by a network of railroads and by atmospheric, hydraulic, pneumatic, electric, and other traction systems; when, in short, I believe that everyone is zealously and sincerely seeking the solution of the problem of reducing as much as possible the difference between the prices of commodities in the places where they are produced and their prices in the places where they are consumed; I should consider myself failing in my duty toward my country, toward my age, and toward myself, if I any longer kept secret the wonderful discovery I have just made.

…

I had this question to resolve:

“Why should a thing made in Brussels, for example, cost more when it reaches Paris?”

Now, it did not take me long to perceive that the rise in price results from the existence of obstacles of several kinds between Paris and Brussels. First of all, there is the distance; we cannot traverse it without effort or loss of time, and we must either submit to this ourselves or pay someone else to submit to it. Then come rivers, marshes, irregularities of terrain, and mud; these are just so many more impediments to overcome. We succeed in doing so by raising causeways, by building bridges, by laying and paving roads, by laying steel rails, etc. But all this costs money, and the commodity transported must bear its share of the expenses. There are, besides, highway robbers, necessitating a constabulary, a police force, etc.

Now, among these obstacles between Brussels and Paris there is one that we ourselves have set up, and at great cost. There are men lying in wait along the whole length of the frontier, armed to the teeth and charged with the task of putting difficulties in the way of transporting goods from one country to the other. They are called customs officials. They act in exactly the same way as the mud and the ruts. They delay and impede commerce; they contribute to the difference that we have noted between the price paid by the consumer and the price received by the producer, a difference that it is our problem to reduce as much as possible.

And herein lies the solution of the problem. Reduce the tariff.

You will then have, in effect, constructed the Northern Railway without its costing you anything. Far from it! You will effect such enormous savings that you will begin to put money in your pocket from the very first day of its operation.

Really, I wonder how we could have ever thought of doing anything so fantastic as to pay many millions of francs for the purpose of removing the natural obstacles that stand between France and other countries, and at the same time pay many other millions for the purpose of substituting artificial obstacles that have exactly the same effect; so that the obstacle created and the obstacle removed neutralize each other and leave things quite as they were before, the only difference being the double expense of the whole operation.

For those of us who strive to communicate economic ideas, it’s humbling to be reminded that Bastiat did it so brilliantly, and with so little impact. If he were alive today, he’d be a hell of a blogger.

Although, he misses the point that you keep emphasizing, which is (I think) that the true cost of the tariff is not the dollar amount of the tariff (which just gets transferred from one party to another), but rather the unrealized gains from the trades that never take place due to the tariff. Whereas the losses due to the transportation costs really were equal to the transportation costs.

So it’s not quite true that if “the obstacle created and the obstacle removed neutralize each other”, then you have “left things quite as they were before”. You could have made things better or worse off, depending on whether the cost to society of imposing the tariff, is greater or less than the dollars paid in tariffs.

Of course he’s still right about the free gains of abolishing the tariff.

Being published in 1845, Bastiat is, of course, out of copyright, and you can read any of his works for free online. e.g. at the Library of Liberty http://oll.libertyfund.org/ (just search for Bastiat Sophisms).

Of course, if you prefer dead-tree format, the Amazon link might still prove useful.

Bennett, I think you’re overthinking the analogy. The simplicity in the idea is what makes it brilliant. Certainly there are greater complexities associated with trade that can be addressed, but the bigger idea of an unnatural obstacle is addressed and identified to readers who may not have realized it existed before in that capacity.

Oh, and Hazlitt in his introduction reckons you’re a day late on the birthday celebrations, although wikipedia disagrees…

No, Bennett is right. The tariff takes money from you and sends it to the gov’t. It’s a transfer. That’s different from a bad road which is just a cost to society.

Now you can argue that there’s a deadweight loss due to the tariff, but Bastiat’s analogy isn’t quite right.

I think he is brilliant.

What I don’t get is how highly intelligent people who are seeking truth can come to exactly opposite conclusions? eg Hayek versus Krugman are both nobel prize winners.

Anytime I read Keynesian critiques, I sit there nodding away thinking “yep yep”.

Is it just that people always bring in their ideologies to investigation no matter how hard they try not to?

Back to broken windows–I saw a story today that the Gulf spill has been a boon for boat builders (they are very busy building shallow-bottomed skimmer boats.) Why hasn’t someone claimed by now that BP, rather than being a villain, should be praised for all the stimulus spending it has created?

An interesting question is why “so little impact.” Stupidity is as ever the answer, but too general; which particular stupidity is it? I suggest that people think mostly about privilege not prosperity. Mnay policies that beggar us all are perfectly sensible if your true goal is to either entrench or dissipate privilege.

He seems to be making some headway – this from a recent UK newspaper:

http://www.independent.co.uk/opinion/commentators/dominic-lawson/dominic-lawson-a-lesson-from-the-napoleonic-wars-2013104.html

However, Keynes did show that there was a little more to it than this, didn’t he?

Expanding on John Faben’s remark about authorized translations of Bastiat’s work being available free online, see also the Library of Economics and Liberty:

Economic Sophisms

Specifically, the paragraphs you quote, in context, begin at Par. I.9.1 and continue at Par. I.9.9.

More works by Bastiat are available on the same site.

I think the Library of Economics and Liberty is related to the Online Library of Liberty cited by Faben.