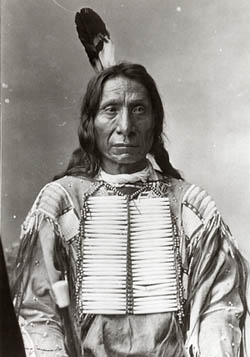

One hundred years ago today, Red Cloud, the last of the great Sioux warrior chiefs, died in peace on the Pine Ridge reservation at the age of 89. He was preceded in death by the way of life he fought so valiantly to preserve.

One hundred years ago today, Red Cloud, the last of the great Sioux warrior chiefs, died in peace on the Pine Ridge reservation at the age of 89. He was preceded in death by the way of life he fought so valiantly to preserve.

If there is such a thing as a just war, Red Cloud’s War of 1866 was more just than most. Black Kettle‘s village of peaceful Cheyenne had been recently and wantonly slaughtered by the Colorado militia under Colonel John Chivington at Sand Creek. (The survivors of this unhappy band would meet their deaths a few years later at Washita Creek, at the equally murderous hands of General George Armstrong Custer.) Against this background, the chiefs had been betrayed at Fort Laramie, where the government had summoned them to negotiate for the right to build roads through Indian territory. With the conference still in session and no agreement in sight, Colonel Henry Carrington and a force of 700 men arrived to build the Bozeman Trail.

It seems to have been Red Cloud who converted thousands of disgruntled but essentially powerless Indians into—well, not exactly an organized fighting force (military organization being pretty much a foreign concept to the Plains Indians), but a force sufficiently coherent and sufficiently aroused to defeat the United States government, first in battle (at Fort Phil Kearney) and then at war. There are conflicting accounts of his military leadership (or lack thereof); it’s more likely that High Back Bone (a/k/a Hump) was the general-in-chief (at least at the Fort Phil Kearney battles). But Red Cloud’s political leadership was paramount; it was about this time that he displaced the hereditary leader Man Afraid Of His Horse as the most influential of the Sioux chiefs.

Whoever led, the attacks on Fort Phil Kearney were devastatingly effective. The Indians, through all their decades of fighting against white soldiers, had exactly one military tactic: To send out a small party of decoys and lead the soldiers into a trap. The Fort Phil Kearney attack was the one and only occasion on which this tactic actually worked. (On every other occasion, without fail, the Indians hiding in ambuscade became overeager and showed themselves while there was still time for the soldiers to escape.) A hundred soldiers under the command of Captain William Fetterman left the fort to relieve a party of wood gatherers; Crazy Horse led the decoys, and the phrase “Fetterman Disaster” entered the national lexicon.

Between the Fetterman fight, a second attack on Fort Phil Kearney, and a series of raids throughout the Powder River Country, Red Cloud’s people devastated the army’s morale and won, in effect, a full surrender from the United States government, which agreed to abandon the Bozeman Trail and the forts that had been built to protect it. All troops were evacuated from the Powder River country and the Indians celebrated by burning the forts. Red Cloud had won the war.

But there were other wars to come. When Red Cloud, who could not read, signed the peace treaty of 1868, he had no idea that the government had inserted a clause requiring the Indian population to move west of the Missouri. As far as Red Cloud was concerned, he had agreed to no such thing. War loomed again.

Now Red Cloud, the great politician, made the first of several visits to Washington, DC to meet with President Grant. Several sources report that Red Cloud requested this visit, but I believe the historian George Hyde, who says that the urgent request came from Washington, where officials were desperate to avert yet another war with the Sioux.

Negotiations broke down when officials flourished the treaty of 1868 and Red Cloud—backed by all the other chiefs in the delegation—insisted that the provision about moving had never been read to any of them. The government then made the great mistake of insisting that Red Cloud visit New York City, hoping to intimidate him with a show of wealth and power. There, Red Cloud gave an impassioned speech at the Cooper Institute (now Cooper Union) that turned the tide of public opinion dramatically in his favor. Once again, Red Cloud had defeated the United States government, which abandoned its relocation plans and asked the Indians to accept an agency on the White River, where they could camp and receive food and blankets.

The hard part was selling his own people on the idea of peace. Having seen their own leaders bamboozled by the white men, many rank and file Indians were prepared to resume hostilities. Red Cloud, the great leader in war, now became the great leader in peace, working tirelessly to damp down the war fever.

For this he was not well repaid by the government, which proceeded in 1875 to steal the Black Hills of South Dakota, which belonged in perpetuity to the Indians in accordance with the Treaty of 1868. Red Cloud offered to sell the Black Hills for $600 million plus food for his people for the next seven generations; the government offered $6 million and no food. As rumors of gold spread and the government did nothing to prevent an influx of white prospectors and miners, it became clear that the Sioux would be lucky to get even that.

(A decade later, in 1883, when the Interior Department tried to expropriate even more Indian lands, the U.S. Congress overruled the action as a clear treaty violation. A Dakota judge immediately ruled that because the Black Hills had already been stolen, and because the Congress had now branded such land thefts as treaty violations, there was now ample precedent to violate all other Indian treaties!!)

The loss of the Black Hills meant war again, though by now it was more Sitting Bull‘s war than Red Cloud’s. Following Custer’s dramatic defeat in this war, the government came to the chiefs with an ultimatum: Give up your lands and move to the Missouri, or we will starve you. There seemed little doubt that public opinion was very different now than it had been after the Cooper Institute speech, and the threat was serious. To save his people, Red Cloud capitulated.

After Red Cloud’s folk had been removed to the Pine Ridge reservation, he continued to his death to resist the white man’s ways, and to dream of restoring his vanished way of life. At the neighboring Rosebud Reservation, his lifelong rival Spotted Tail took the opposite tack, encouraging his people to prepare for a new and very different future.

Fascinating! :)

He should have bargained for access to education and capital investment. If Custer had attacked with textile machines and modern plows instead of guns there would have been fewer deaths and the Native people could have made their own blankets.

In 2002, then Senate Majority Leader Tom Daschle was in a close campaign with Republican John Thune. Tim Giago from the Pine Ridge reservation announced that he would run for the Senate as an independent candidate. Democrats in South Dakota usually get an overwhelming majority of the vote on the Lakota reservations, and in a close race, losing a big chunk of that to Giago meant Daschle would certainly lose to Thune. Shortly before the election, they worked out a deal: Giago would drop out of the race and endorse Daschle, and in exchange, Daschle would use his influence as Senate Majority Leader to get Congress to return the Black Hills to the Lakota (aka Sioux).

Unfortunately, the 2002 election was a Republican wave, and Thune ended up narrowly beating Daschle anyway, so the deal came to naught.

The last paragraph in this piece is very moving. Great story.